Imagine you were told you would deliver your baby on November 19, but you go into labor on October 19 – a full month before you anticipated. Do you know how you are getting to the hospital? Have you saved enough money for unforeseen hospital costs? Who will watch your small children? Now, imagine that it will take the nearest taxi driver at least 30 minutes to get to your home, you have no cell phone to contact them, and it is the middle of the night.

Our recently published paper in BMC Health Services Research shows that errors in estimated delivery dates are prevalent in Zanzibar, Tanzania. We found that these errors led to lower rates of health facility delivery.

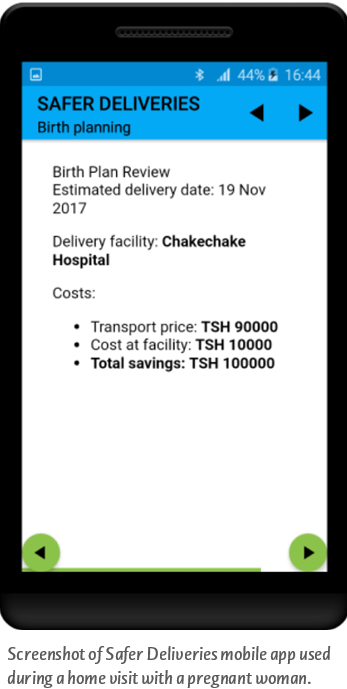

Back in May 2017, I arrived at the vibrant Zanzibar D-tree office with my colleague, Kaya Hedt. At this time, D-tree had just celebrated the enrollment of 10,000 pregnant women in the Safer Deliveries (Uzazi Salama) program, which equipped community health volunteers (CHVs) with a digital tool to increase delivery rates at health facilities, referral completions, and postnatal care-seeking behaviors. Our goal for the next twelve weeks was to lead a data analysis training course for D-tree and the Ministry of Health team members, while also investigating the predictors of health facility delivery among women enrolled in the program.

When digging into the data, Kaya and I made a perplexing discovery. We realized that almost half (43%) of the enrolled women had a preterm birth according to their estimated gestational age at delivery. For reference, it is estimated that only 10% of babies are born preterm in Tanzania, with other regions reporting preterm birth rates between 2% and 15%.

The two common methods for estimating gestational age are date of last menstrual period (not-so-gold-standard) and ultrasound machine (gold standard). As ultrasounds are not available in many low-resource settings, studies have investigated the differences between these methods, suggesting that dating by last menstrual period (LMP) should yield similar estimates to the ultrasound. However, this requires that the date of LMP is accurately recalled. In the Safer Deliveries program, this is likely not the case due to a variety of factors, most notably that this date is often assessed months into pregnancy during an antenatal care visit. “From my experience living in Zanzibar, cultural beliefs can be one aspect of mothers failing to provide the right information for their LMP in getting the right [estimated delivery date],” said Jalia Tibaijuka, former nurse and Senior Program Coordinator on the D-tree team in Zanzibar and co-author on the paper. “Women never want to expose themselves to early pregnancy…If they are recognized in the early pregnancy stage, pregnancy can be terminated either by witchcraft or with people having ‘evil eyes.’ Due to such a situation, the mother may attend antenatal care [visit] late.”

We found that women who delivered “early” compared to their estimated delivery dates had fewer CHV home visits, saved less money for delivery on average, and were less likely to deliver in a health facility. Indeed, some of these early deliveries may truly be preterm births. For these women, it is critical that we can correctly identify their births as preterm so they can receive the necessary interventions. However, for the majority of these women, we believe the early deliveries were due to errors in estimated delivery dates, which we now know has negative consequences. Either way, improvements in the estimation of gestational age will lead to better health outcomes in both groups of women.

Since the findings of this study, we have formulated a list of ways to either improve estimation of gestational age or curb the effects of the errors in gestational age measurements. For the former, we considered decentralization of ultrasound technology to health centers, use of portable ultrasounds by trained CHVs, or training CHVs and health workers on techniques to aid LMP recall. These potential solutions will be tested to assess feasibility and effectiveness during expansion of Jamii ni Afya—a nationwide digital community health program, supported by D-tree, which is being rolled out by the Zanzibar Ministry of Health as part of the revised National Community Health Strategy. For now, CHVs are emphasizing that estimated delivery dates are just that – an estimate – and are often subject to error.

Isabel Fulcher is a post-doctoral fellow in the Harvard Data Science Initiative program at Harvard University who has been working closely with D-tree International around data analysis and research in Zanzibar.