In a sparsely furnished room on a side street in the Kibaha district outside of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Ally Maandiko shuffles through loose patient forms, setting aside the ones he’ll need during his visits for the day. He shifts slightly in his seat to allow more sunlight to reach the forms and adjusts his glasses. Even after twenty years of doing this work, he still wakes up every morning to the familiar pull to serve. To Ally, there’s no more important job than the one he’s doing right now: using his experience with countless organizations and programs to help his community navigate the healthcare system. Nonetheless, Ally is no stranger to the challenges of his job, and he knows there’s a good chance that the people he sees today—his friends and neighbors—won’t receive the high-quality care that they need and deserve.

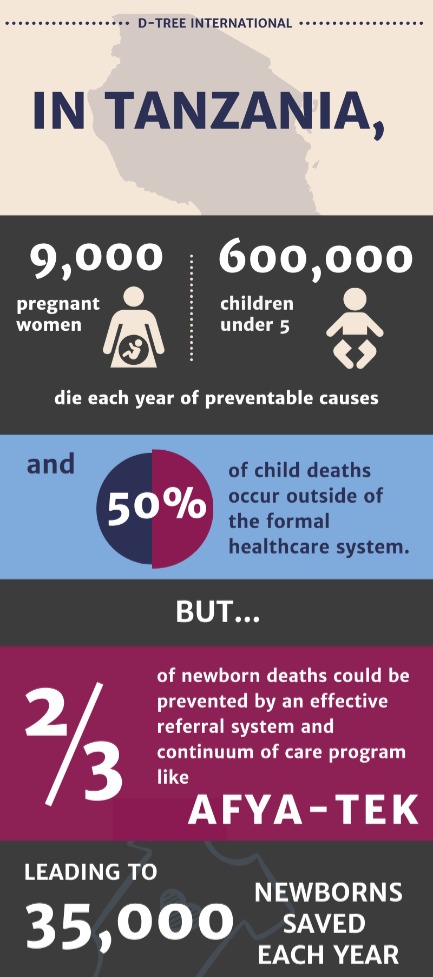

Community health volunteers (CHVs) like Ally have been critical in improving access to healthcare in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); however, though global access to healthcare has steadily improved, the quality of that care has not necessarily followed suit. A staggering 15.6 million people in LMICs die each year from preventable causes, and 55% of those can be attributed to poor-quality healthcare. High-quality care is possible, even in the most remote areas, but it requires the holistic strengthening of entire health systems—which is no small task.

In Tanzania, the healthcare system at the local level is divided into three main actors:

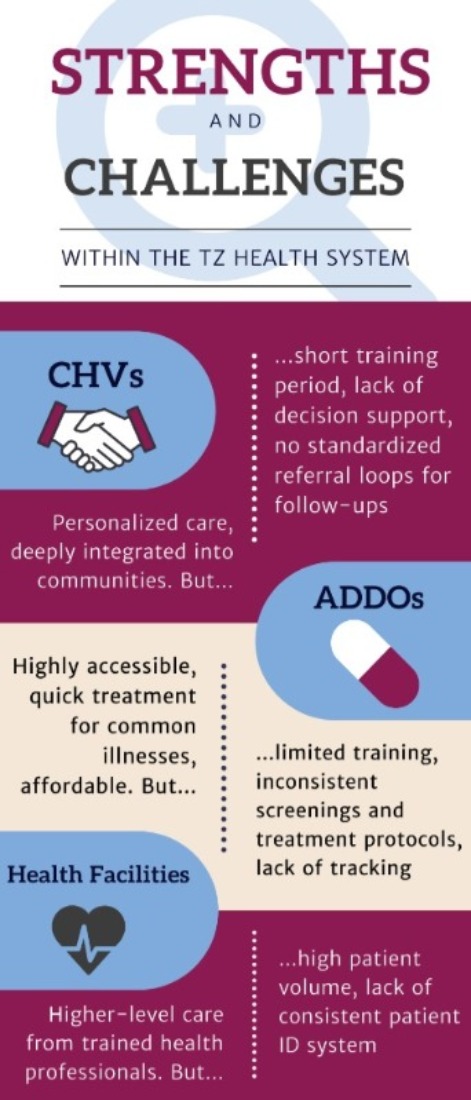

1. Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) like Ally are community-appointed health workers who assess patients, often through household visits, and either direct them to an Accredited Drug Dispenser Outlet (ADDO) for minor illnesses or refer them to a health facility for more serious conditions. CHVs do not carry medications, so their role is to identify, assess, advise, and refer. They are at the front lines of the local healthcare system—a crucially important role, as around 50% of child deaths occur outside of formal healthcare.

2. Accredited Drug Dispenser Outlets (ADDOs) are private dispensers of medications and basic first aid services. ADDOs have a higher level of expertise than CHVs and defer to guidelines provided by the Pharmacy Council when screening and treating patients. ADDOs are easily accessible in rural settings, making them the primary access point of healthcare for many people in these areas.

3. Health facilities are clinics, dispensaries, and health centers staffed with healthcare professionals. Doctors and nurses at these facilities are more experienced than ADDO dispensers and CHVs and offer the most comprehensive treatment; however, with an average catchment area of around 50,000 people, health facilities are often far away and understaffed.

In addition to the individual challenges faced by these three actors, there are several universal challenges that undermine the quality of the entire system and lead to fragmented care:

-

The current paper-based referral system is inconsistent and unreliable. CHVs and ADDOs are trained to use specific forms when referring patients to the health facilities; however, oral referrals and scrap paper often take the place of these forms due to shortages of referral books or confusion about how to use them.

-

Because of the inconsistencies in the referral system, CHV follow-up appointments after ADDO or health facility visits are difficult to track.

-

Very few people are registered in the national paper ID system, meaning patients lack unique identification. This leads to misidentification of patients, loss or duplication of data, waste of resources, and errors in diagnosis and treatment.

-

CHVs and ADDOs lack the critical decision support that would enable them to accurately diagnose, treat, and refer patients as necessary.

THE AFYA-TEK PROGRAM

This program is funded and supported by Fondation Botnar, which champions the use of AI and digital technology to improve the health and wellbeing of children and young people in growing urban environments, and aims to deliver an innovative digital solution to the challenges faced by CHVs, ADDOs, and health facilities via harmonized digital applications tailored to each actor. Designed by Apotheker Consultancy, a local firm, in coordination with D-tree International, local and international partners, and the Ministry of Health, the intervention goals are two-fold:

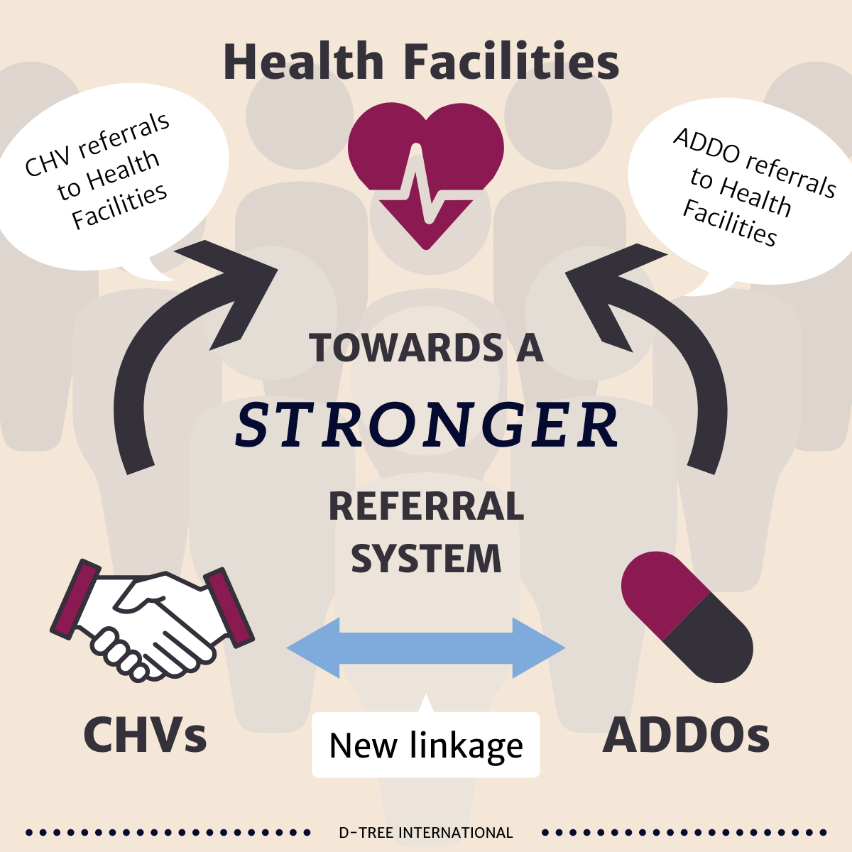

1. Improving the continuity of care. Afya-Tek’s digital platform provides a linkage among the three main actors of the primary health system, allowing for a more consistent continuum of care. Using a fully-digitized referral system conducive to areas with low network connectivity and unreliable access to electricity, CHVs and ADDOs will be able to efficiently refer patients to the appropriate service, track their status, and follow up to ensure proper, respectful treatment. Afya-Tek’s system will be developed on the Open Smart Register Platform (OpenSRP), the open-source software currently designated by the Tanzanian government for all community health information systems.

2. Improving the quality of care. In addition to program-level coordination of care, Afya-Tek will also provide decision support in diagnosis, treatment, and appropriate referral procedures. Applications will offer government-approved screening protocols for danger signs, empowering CHVs to quickly recognize a problem as it arises in the home and enabling ADDOs to provide accurate pharmaceutical services. As patients arrive in each locality, unique biometric identification through fingerprint scanning will enable the system to not only increase efficiency and consistency of treatment through patient tracking, but it also will prevent valuable patient information from being lost or unnecessarily duplicated. Then, with each referral, automated follow-up tasks will facilitate more consistent follow-ups from CHVs.

No other current intervention has been able to link ADDOs, a private entity, with the public CHV and health facility systems; nor have similar programs engaged with adolescents. Afya-Tek will be the first to do both, offering a fully coordinated referral system among CHVs, ADDOs, and health facilities. Closing these referral loops is foundational to delivering diligent, efficient care and ensuring that patients don’t slip through the cracks.

CURRENT PROGRESS

In its “Proof of Concept” phase, set to kick off in April 2020, Afya-Tek will be centered in the Kibaha District outside of Dar es Salaam and will focus on three specific populations, targeting the most critical threats to each: children under five years old (pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria); prenatal and postnatal mothers (danger signs such as hypertension), and adolescents (family planning services).

Pivotal to the success of Afya-Tek is its unique human-centered design approach. The D-tree team’s formative field research from May to September of this year has engaged beneficiaries, health care workers, ADDOs, and the government in the conversation from the very beginning, ensuring that the needs of the community are understood, respected, and addressed. Through hours of interviews and focus groups with CHVs, ADDO dispensers, and Health Facility workers, we gained a clear understanding of the current system and how Afya-Tek might fit in.

Using the information from this field research, we are now focused on developing the system by first defining the technical requirements—essentially, the mold into which the system will be poured—in full coordination with our partners: Apotheker, the main project lead; Simprints, responsible for contributing the biometric fingerprint scanning technology; Ona, the technical lead for OpenSRP; the Institute for Tropical Medicine (ITM), tasked with evaluating program activities and outcomes and with capturing learning to adapt the program; the President’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government (PORALG), a government partner overseeing community health information system design; and Inspired Ideas, assigned to the introduction of artificial intelligence to ADDOs.

“By joining forces, the local and international Afya-Tek partners can truly embrace cutting-edge technologies in an innovative approach to strengthening a health system, especially to respond to the health needs of children and adolescents.” — Siddhartha Jha, AI/Digital Program Manager at Fondation Botnar

“[As a CHV, I was] very pleased by the first step you took,” Ally reflected during one of the field research interviews. “You tried to understand what it is that we do, and what are our needs, so that you can anticipate the challenges we might face once the program is implemented and be able to intervene appropriately.” Indeed, this human-centered design approach is the very crux of Afya-Tek’s potential to invigorate the Tanzanian healthcare system, as it brings with it the promise of a strong sense of ownership, accountability, and coordination among all parties as the program unfolds. Only by strengthening the healthcare system in this holistic, multi-level way will the quality of care improve as the world moves toward its goal of Universal Health Coverage. Only through the implementation of a digital system like Afya-Tek can dedicated healthcare workers like Ally Maandiko deliver the efficient, respectful, patient-centered care that his friends and neighbors deserve.

Dillip, A., Kimatta, S., Embrey, M., Chalker, J. C., Valimba, R., Malliwah, M., … & Johnson, K. (2017). Can formalizing links among community health workers, accredited drug dispensing outlet dispensers, and health facility staff increase their collaboration to improve prompt access to maternal and child care? A qualitative study in Tanzania. BMC health services research, 17(1), 416.

Haskins, L., Grant, M., Phakathi, S., Wilford, A., Jama, N., & Horwood, C. (2017). Insights into health care seeking behaviour for children in communities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. African journal of primary health care & family medicine, 9(1), 1-9.

Ministry of Health, et al. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and Malaria Indicator Survey: Key Indicators. 2015-2016.

Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries (Kruk et al. 2018)