Working with the community can be challenging. Our people are set in their ways. While they may have the information they need, they often lack the deeper understanding needed to make the right decisions.

Asya, Nurse, Zanzibar

Asya has been a nurse in Zanzibar for 13 years, dedicated to mothers and children. But she’s frustrated. Women arrive late in pregnancy, miss critical checkups and struggle to follow medical advice.

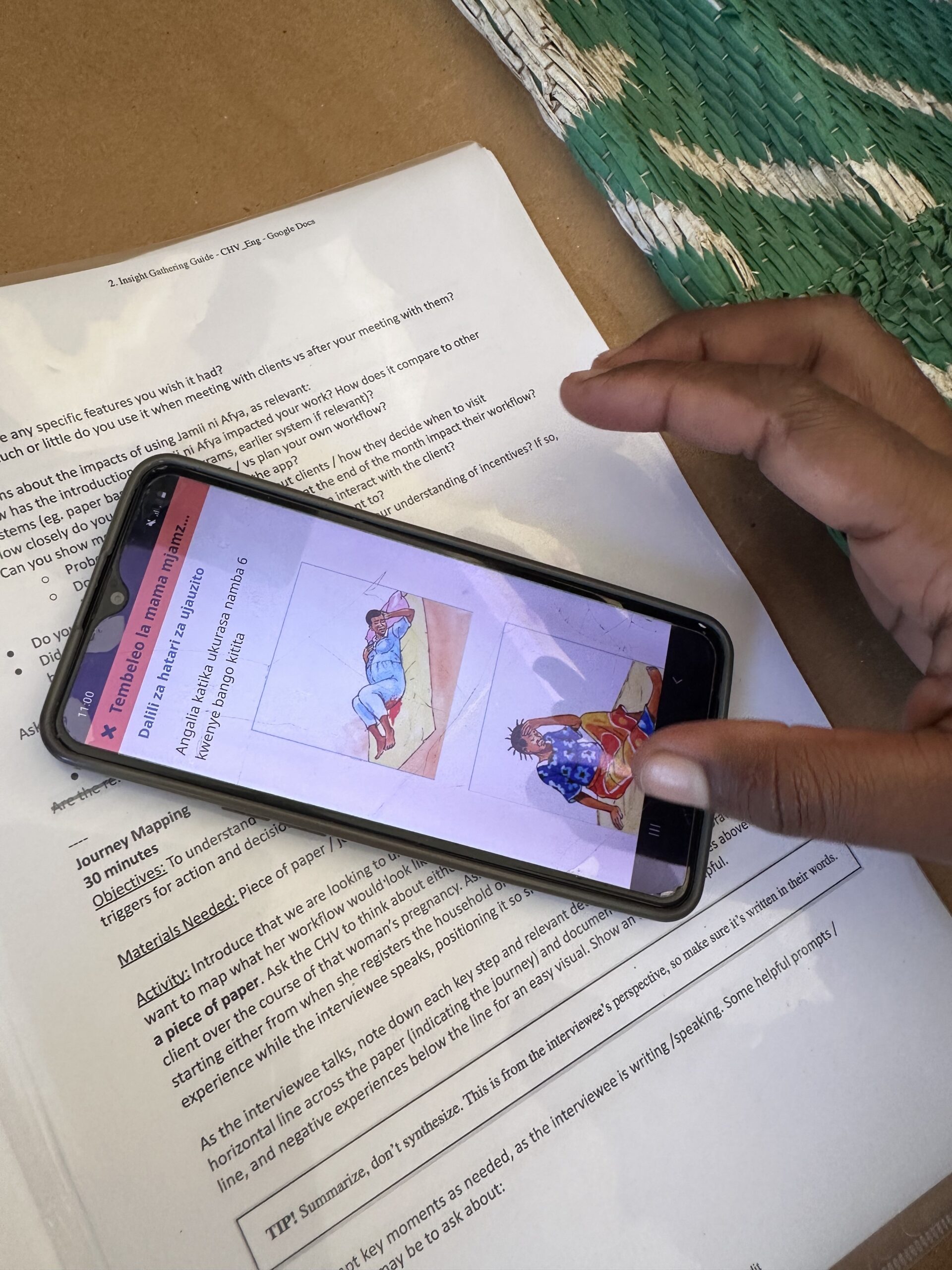

At the clinic, Asya is overwhelmed. Time constraints for each visit drive consultations short, making it difficult to take medical histories, which can impact the type of care provided. Supply shortages add to the challenge, eroding trust with the very community she’s determined to serve. Her struggle isn’t unique – it’s the daily reality for countless healthcare providers in Zanzibar and beyond.

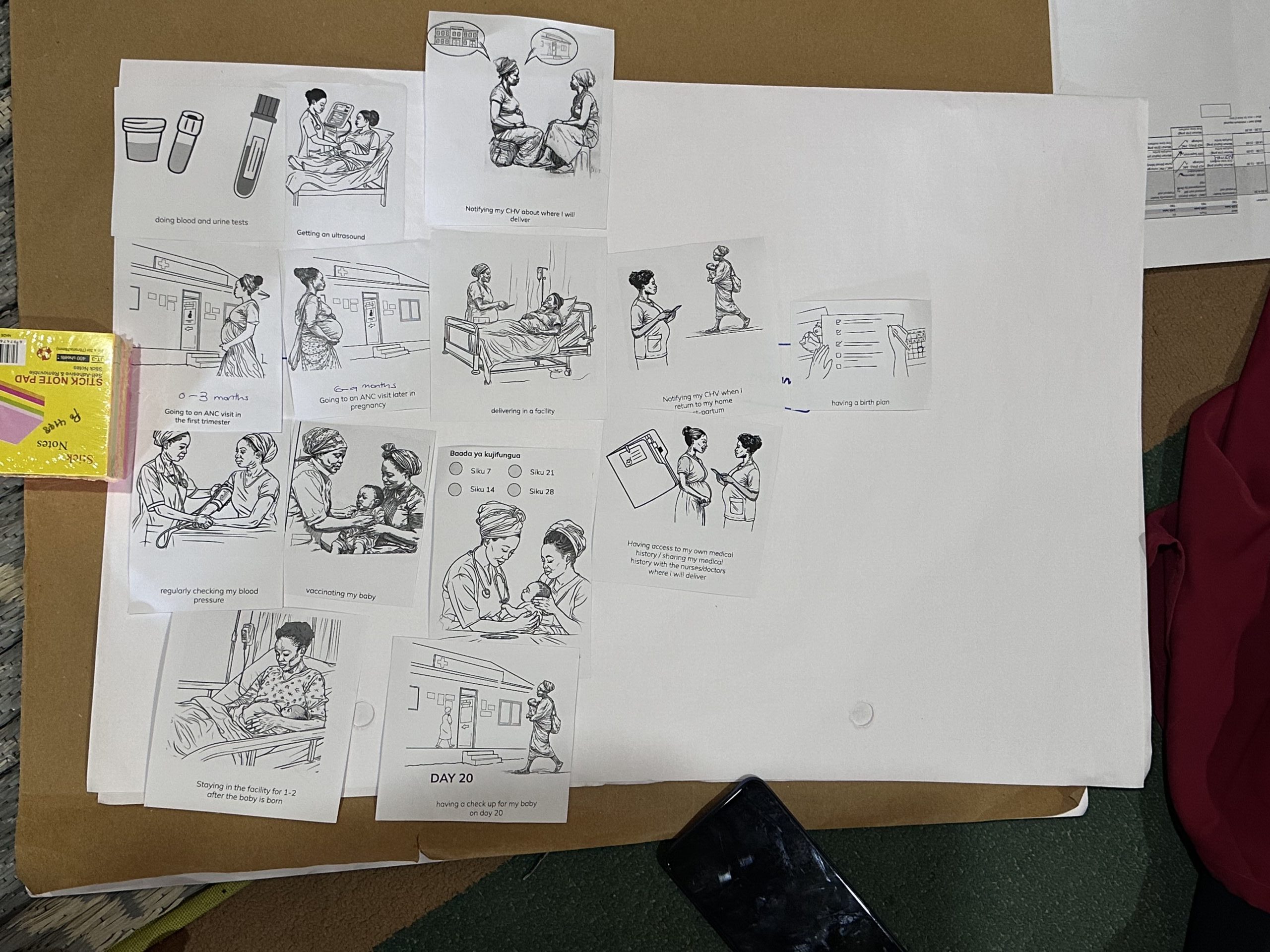

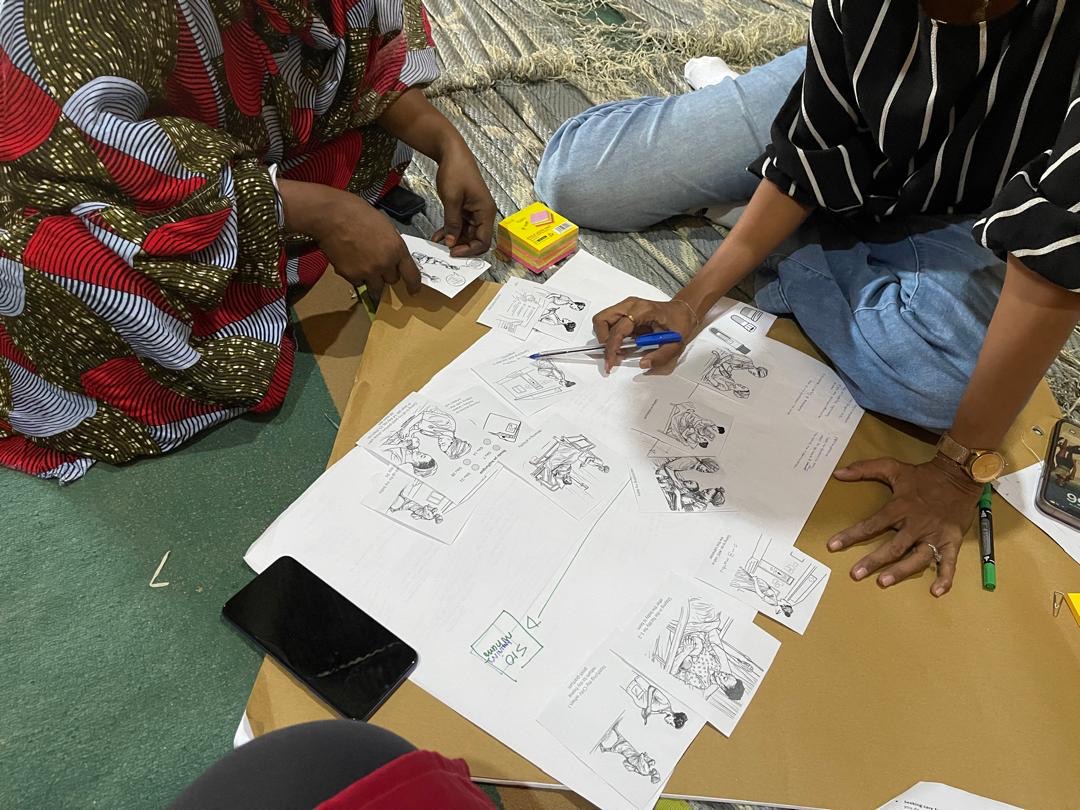

Last year, D-tree set out to uncover how culture and behavior shape pregnant women’s access to healthcare in Zanzibar. Partnering with a creative design agency, Khanga Rue, we went deep – speaking to mothers, healthcare workers and community health providers – to expose barriers, gaps and opportunities. The insights are now shaping Jamii ni Afya, Zanzibar’s national digital community health program, and improving our people-centered care approach to better serve women from pregnancy through postpartum.

Insights from the study

Few women see a formal healthcare provider early in their pregnancy

Most women know it’s recommended to see a healthcare provider early in their pregnancy, but in Zanzibar, few do. Why? For many, the reasons to delay outweigh the motivation to initiate an early check-up.

Women are told to visit a clinic in the first trimester, but are rarely told why it matters. Their role models – mothers, grandmothers, and mothers-in-law – gave birth at home, with little contact with health facilities. Without a clear understanding of early check-ups’ life-saving value, cultural and social norms take over, delaying care. By the time they seek help, it may be too late to catch complications or plan for a safe birth.