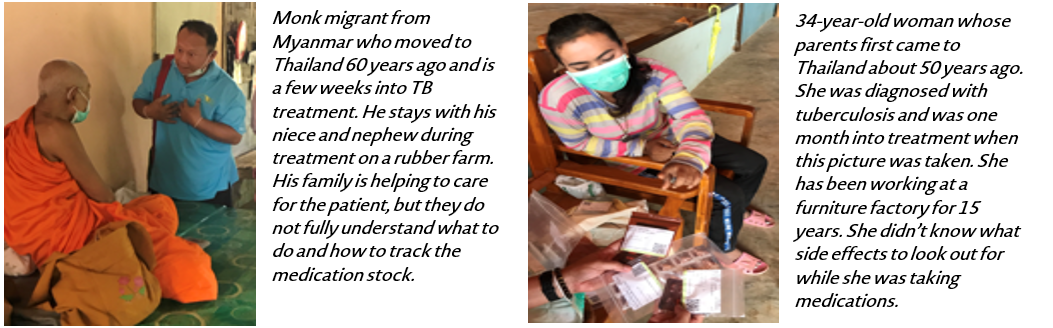

A year ago, I visited western Thailand with American Refugee Committee at Alight , a nonprofit organization working to improve lives of refugees, displaced persons and migrants, to design a program for migrants who have tuberculosis. The program is funded by TB Reach Wave 6, and works to address challenges related to lack of consistent care and access to tuberculosis medications, particularly an issue because migrants in Thailand often move around for work and lose touch with the health system. If a TB patient loses touch with the health system before the 6-9 months of treatment is complete, there is a large risk that a tuberculosis case will worsen and become drug resistant, and also spread to other people that the patient comes into contact with.

Through an initial design visit, the American Refugee Committee team and I spoke with migrant patients and health volunteers and discovered key challenges to tuberculosis care among migrants:

-

It was difficult for health volunteers to track patient care for those who move away or travel across the Myanmar border, especially using the traditional paper-based system

-

Patients and caretakers do not fully understand tuberculosis treatment and the medication regimen, including the length of treatment and side effects

-

Patients were hesitant to visit the health facility, because there was a language barrier between the Myanmar migrants and the health worker and potential for discrimination

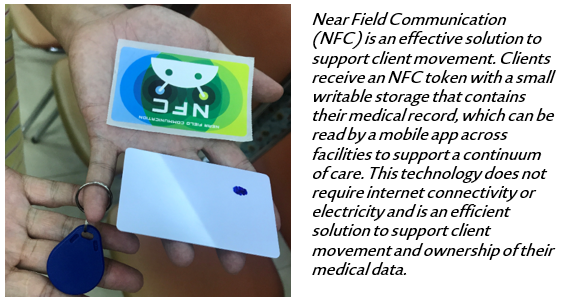

Recognizing the unique characteristics of migrant patient movement and the need for long term care for tuberculosis treatment, we designed a solution which addresses these challenges using Near Field Communication (NFC) technology and a Mobile application. In the program, the Migrant Liaison Officer is a supervisor who uses a mobile application to enroll a patient into a 6-month program (with the patient’s consent) and to supervise Migrant Health Volunteers to make sure he/she is meeting with patients. The Migrant Health Volunteer visits the patient regularly at home, and guided by a mobile app with decision support, administers tuberculosis medications and evaluates patient side effects. After a visit, the health volunteer taps an NFC tag onto the back of the mobile phone, which stores the patient information from the mobile application onto the NFC tag, and leaves the NFC tag with the patient. The patient holds onto the NFC tag and brings the tag with him/her to any future visit with the program. This way, even as the migrant patient moves across low connectivity settings within and even outside of the patient’s district, the patient’s data is available during the visit. With this solution, any health volunteer in the program can read the NFC tag and pull up the latest patient information to continue the continuity of patient care.

We chose Near Field Communication as a critical part of the solution for several reasons:

1. Supports patient movement. A large challenge in managing migrant patients is loss to follow up. Patients often move away or transfer out of the system and therefore default on treatment. The NFC and mobile application system provides a way to track patients who transfer out of the program, and also enables users to transfer complete patient records from one district to another using NFC scanning.

2. Allows for multiple health workers to access a case. Often with digital health programs, it is difficult to share data across health workers for a variety of technical reasons, which therefore limits continuity of care if more than one health worker needs to visit a patient. With access to the latest patient information on the NFC token, data sharing across health workers is easier to maintain, and we can support multiple health volunteer – patient relationships. Additionally, though data are shared among assigned health workers for patients care, the confidentiality and security of these data are maintained through different usernames and passwords.

3. Facilitate patient record retrieval. Similar to QR codes, the NFC token contains a unique identifier that can be used to retrieve the patient record. This is useful in settings where health workers interact with a large number of patients and where it thus would be difficult to retrieve a record from a complete list, or even through a search function that might fail due to differences in spelling or typos. We have seen from many other programs that identifying clients using names or typed ID numbers is extremely problematic and can lead to duplicate registrations of up to 50% of clients. It is therefore important to have a truly unique ID to identify a client.

4. Works in low connectivity settings. With very low, or no, connectivity in some villages in Thailand, NFC provides a solution to lack of connectivity, since it can work in such settings. Health volunteers with the program’s mobile application can read the NFC token offline and pull up the latest information to continue care; they do not need to rely on connectivity to view the latest patient record since it is always stored on the NFC token.

5. Solution is client centered. The NFC token stores client data, so the client can carry the data with him/her to any patient visit and is empowered to own the data when moving across locations. This is different than other forms of identification such as biometrics and QR codes which does not store client information directly, but instead acts as an identifier to pull a record from a mobile application

6. Language-independent. The NFC token is language-independent, which means that a mobile application can display information from the NFC token in whichever language the user selects for the application. This helps to solve the problem of client movement to an area with a foreign language, because if the client moves to a different area, the NFC could be read by the health worker in the health worker’s own language.

7. Data is secure. The NFC token is encrypted, and therefore, information on the NFC token can only be accessed from a phone with the compatible program mobile application. If the NFC token is lost, it cannot be picked up and read by another system, and is only available for the authorized health workers within the program. Since the program works with vulnerable migrant populations, this was a critical component for selecting this solution.

8. Low cost. The price of an NFC token is as little as $1 per patient for a variety of different NFC formats: bracelets, stickers, cards and keychain tags. This makes NFC attractive for scalability.

Throughout the program, we recognized the importance of undergoing thorough design, testing and usability activities unique to the NFC program.

We discovered during design, that users and patients have unique preferences related to NFC. In particular, NFC tokens come in a variety of different formats, and considering the culture and the context, we identified which type was most appropriate for patients. Patients preferred using keychain tags stored on necklaces, instead of cards because they felt that they would lose the cards easily. We also defined the key workflow touch points for NFC, most importantly during the home visits when the users need access to adherence information, and during patient transfer when the system needs to move an entire case from one location to another.

During system testing, we focused on NFC type and phone compatibility and usability for users and patients, since not all phones are compatible with all NFC types. We also replicated real-life testing as much as possible, and tested without connectivity, similar to the low connectivity rural villages. A key part of our testing was end user testing and patient feedback to identify enhancements to NFC scanning, and we then updated the system based on the feedback to add more pictures and visual cues for scanning

During training, we wanted to make sure that users were comfortable scanning NFC and understood when and how to scan. We practiced NFC scanning skills and troubleshooting during training, and shared training videos so the users could review how to scan, even after the training sessions were over.

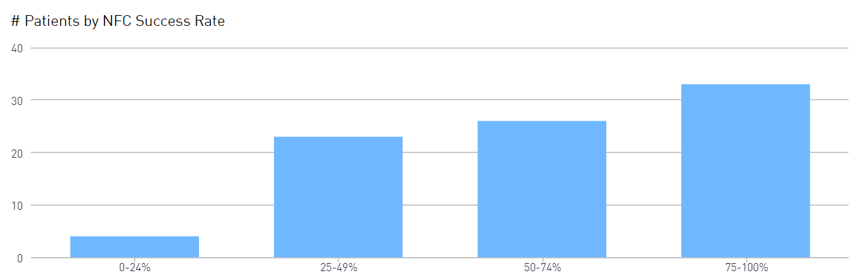

After implementation, we analyzed user feedback to see the trends of NFC use, and worked with our partner, American Refugee Committee, to follow up with users. Specifically, we evaluated the NFC scan success rate (number of success NFC scans / the number of NFC attempts) and also user feedback related to ease of use of both the mobile application and NFC. This data provided the American Refugee Committee team with information about which users were having trouble scanning NFC and needed follow up.

Where are we now, and the potential for Near Field Communication solutions:

So far, 83 migrant patients have been registered in two regions on the western border of Thailand- Kanchanaburi and Tak. Among those patients, we see extremely high medication adherence at 99%, which is 16% higher than the national target for treatment success. Through the system, we are able to track that three patients were transferred out of the intervention locations, and one patient was transferred within the intervention locations, a key functionality considering the challenges related to transfer and loss to follow up. Currently 10 patients in the program are cured, and we are continuing to monitor the treatment success of the patients through the end of the program into 2020.

Furthermore, we continue to improve on the solution as we receive feedback from end users and analyze the program data to support better use of NFC activities and data sharing across users and locations.

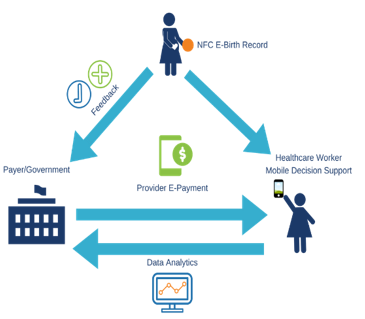

NFC use for long term case management such as tuberculosis treatment sets the stage for other health issues that require long term continuity of care such as chronic condition management, maternal health and immunization tracking. For example, we developed a solution using mobile and NFC technology with Open Development, a global development organization, to support maternal health care continuity and payment transparency in Liberia across public and private health systems.

Additionally, patient movement, identification and low network connectivity are challenges across a variety of scenarios including cross-border movement and fragile states. We see significant potential to bring this type of solution to fragile states, particularly humanitarian settings, which need clear patient identification and tracking for vulnerable populations. By carefully designing, developing and deploying solutions for the specific context, Near Field Communication can be a great addition to disrupt the way that records and care are managed in these scenarios.