This post is part of our ongoing Digital Spark series. Be sure to also check out the series introduction as well as the other posts in the series: health systems strengthening , embracing collaboration, data protection and privacy, and lessons from COVID-19.

Lela carries her 6-year-old son, Khari, to the health center for the fourth time this month. His fever keeps returning and, although he has been treated every time, he keeps getting sick. Lela can’t afford to go to the health center every week since it means that she loses a day of work and even has to pay for the medicines that are being given to Khari. Maybe this time will be different.

At the health center Lela signs in and sees the nurse, Jalia, who says: “It is the rainy season so there is a lot of malaria. We could just keep treating him as that is probably what this is. But we just got something new to help us diagnose Khari, so let’s see what it says.”

Jalia takes out her new phone and registers Khari. She enters that this is the fourth time in a month that Khari has been in with a fever. However, rather than just say that Khari’s illness must be malaria, the app on the phone tells Jalia to do a simple blood test. After a few minutes, Jalia is surprised to see that the test says it is not malaria. The app suggests checking for ear problems, cough and other problems that sometimes cause fever. It also prompts Jalia to ask about other family members who are sick and finds that Khari’s grandma, who lives in the same household, has been sick and coughing for months. Jalia also sees that Khari has been losing weight for the past few months and wonders if there is something other than recurrent malaria that she should investigate. As a result, she suggests that Khari be taken to the district hospital 15 kilometers away and uses the phone to arrange transportation. Fortunately, there is a new government program that allows Jalia to call a local driver and take Lela and Khari to the hospital.

One month later, Khari is doing well. He was diagnosed with Tuberculosis at the hospital, and now he and his whole family are on treatment.

Digital Health is different

Khari is a lucky boy. Because Jalia had been part of the new digital health program in her country, she was able to:

-

know that Khari had been to the clinic multiple times and was losing weight;

-

correctly diagnose the problem;

-

show a short video to Lela to explain why she needed to go to the hospital;

-

arrange transportation immediately so that Khari would get the appropriate care; and

-

follow up with Grandma and other family members and provide the appropriate treatment to everyone.

No, technology is not a divine tool sent to solve every health issue worldwide. It is not magic. But it does change how a health system functions. Yes, we are surrounded by a mountain of failed digital health pilots, most notably resulting in a digital health moratorium in Uganda in 2010—but what’s emerged from the rubble is a better understanding of how digital devices can positively disrupt health systems worldwide.

No, technology is not a divine tool sent to solve every health issue worldwide. But it does change how a health system functions.

So, what have we learned from all these “failed” experiments? We have learned that health workers are human, and even with the best training they can make mistakes; that systems change does not happen overnight, and a project lasting only a few years will not get the necessary buy-in from governments, health workers, or program managers to reach their full potential; and that health workers are supportive of innovation if it helps them do their job more efficiently—they are busy, and saving time while improving quality is a welcome goal.

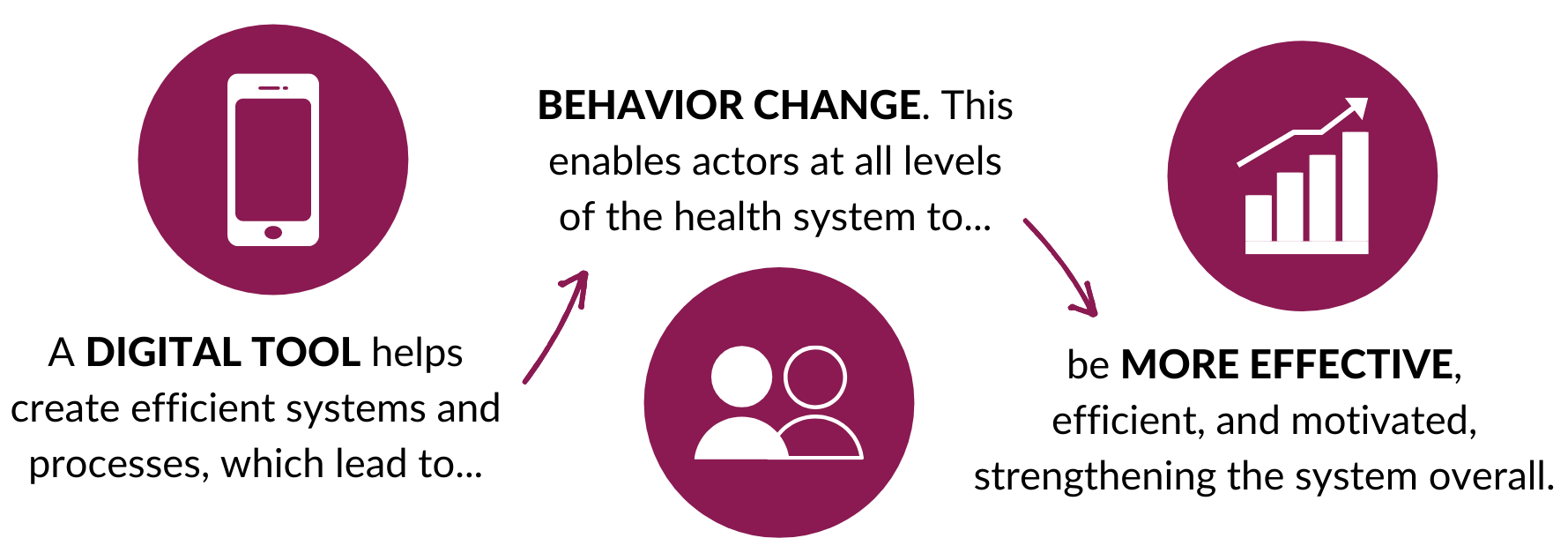

Above all, we have learned that digital health cannot fix a broken system; in fact, in many cases a digital system simply puts a magnifying glass on the existing problems within a health system, from pervasive stock-outs to client mistreatment. A successful digital health intervention, on the other hand, would look like this:

The critical element in this process, the piece most often missed in ill-fated interventions, is this: it’s the people within the existing local system who empower health system changes. To build and deploy a digital system without taking into account human processes is to disregard the complexities of that health system. This idea has been a cornerstone of D-tree’s programs, as we act as the bridge between the innovative technology and the public health needs and cultural contexts in the communities where we work. We believe that in practice, meaningful systems changes have little to do with the technology, and everything to do with human-centered approaches such as high-level advocacy, engagement with actors at all levels, ongoing capacity building, and policy changes.

What’s more, trying to put together a system piecemeal will not have the desired effect. Digital systems must be integrated both vertically and horizontally, with organizations and governments working together from the outset to ensure buy-in and sustainability. Take, for example, D-tree’s program in Zanzibar, Jamii ni Afya—a nationwide community health volunteer program that utilizes technology as the foundation of the care delivery and monitoring system and has now been fully integrated into the national health system of Zanzibar.

The Jamii ni Afya program has followed a Human-Centered Design process, involving the government of Zanzibar in planning, strategy, implementation, and continued monitoring and management. The digital system was also integrated both horizontally and vertically. Across the horizontal community level, the program strengthens health service delivery by equipping Community Health Workers (CHWs) with a powerful digital tool that supports the high-quality delivery of a wide breadth of services, including nutrition, early child development, and Reproductive Maternal Neonatal and Child Health. The program is also vertically integrated, connecting those CHWs at the community level to actors at the district and national levels, who then use the data collected to drive decision-making. This engagement at all levels has ensured that the digital system was not put together piecemeal, while collaborating with the government from the outset has served to bolster government capacity and promote long-term community sustainability of the program.

Digital Health is working, but why?

In 2018, for the first time ever, the global number of people who used mobile internet (3.54 billion) surpassed those who did not within areas with network access. In low- and middle-income countries, mobile is the primary means of accessing the internet, with an average of 57% of people who use the internet accessing it exclusively on mobile phone. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, where connection rates are the lowest in the world, more than 80 million people gained access to mobile internet in 2018 alone. Clearly, internet access is expanding globally, permeating even the most hard-to-reach places.

The rise of mobile internet usage opens the door for meaningful digital health interventions due to four main implications of shifting to a digital landscape:

i. Instant data and real-time tracking

Digital health means that data sharing and real-time tracking can be bi-directional between the community health system on the ground and the district or national management system making health-related decisions. When data flows from devices at the community level up to these oversight bodies, leaders and decision-makers can survey the community-level data in a dashboard and use the evidence on the ground to inform policies going forward.

An intriguing example of this real-time tracking comes in the form of a smart digital thermometer made by Kinsa Health. Kinsa’s thermometers are paired to a mobile app, which can record temperature and symptom data and send this information to Kinsa’s database. While in the past Kinsa used this technology to track the spread of seasonal influenza, it proved useful in predicting outbreaks and observing trends in the spread of COVID-19 across the US in the first weeks and months of the pandemic. Aggregate data, taken from up to 162,000 temperature readings per day, were then used by state and federal governments in determining to what extent social distancing measures were effective in reducing the spread of the virus.

Data can also flow in a top-down direction, making possible the real-time release of updated information or policies from decision-making bodies. In this way, health workers on the ground can stay informed on which medications or vaccines are locally available, for example, or on which medications or vaccines are recommended by international guidelines.

ii. Continued guidance for healthcare workers

Digital health also presents opportunities for healthcare workers to receive continued guidance or training over time. In many developing countries, healthcare workers within communities undergo only a short period of training. Digital health offers a way for healthcare workers to easily continue their education, refresh concepts or practices they haven’t used in a while, and quickly receive updated guidance. For example, as part of its Community Health Academy launched in 2017, Last Mile Health has developed an application with real-time educational text, quizzes, and videos for use by CHWs. The application content will be offered as a global good for local adaptation and deployment by Ministries of Health all over the world.

The rapid dissemination of updated information is especially important in fast-paced scenarios like outbreaks or epidemics, such as in the Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016 or in the COVID-19 pandemic. In these situations, when the information and response landscape is constantly shifting, real-time updates on identified cases, new findings about the disease itself, or developments in treatment strategy are crucial for an accurate response and for saving lives.

Digital health offers a way for healthcare workers to easily continue their education and quickly receive updated guidance.

iii. Efficiency of service delivery

Still, faster transmission of information doesn’t necessarily mean more efficient service delivery. Once a community health worker has updated information, what does she do with it? In many areas of the world, CHWs are faced with daunting paper protocols for assessing and treating patients and burdened with stacks of referral and reporting forms. The shift to digital health means a shift away from these massive paper protocols that are often difficult to navigate. A digital tool is client specific, using information gathered from previous and current visits to offer tailored services. It shows only information relevant to the client and provides a step-by-step guide for the CHW, whose job it is to act as the human link between decision support and more efficient, higher-quality care.

iv. Integration with other technologies

Finally, a digital tool holds great potential for integration with other technologies. Digital health systems are agile and can manage multiple layers and intricacies of the health systems, serving as more than just a reiteration of treatment protocols. It presents opportunities for integration with other technologies to vastly improve care through advancements such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and biometric identification. We’ve already seen the promise of these technologies to vastly improve the quality of care.

-

As part of the Jamii ni Afya program in Zanzibar, we are employing predictive analytics and machine learning to predict threats to expectant mothers. This integration allows local community health workers to quickly and efficiently identify women who may be at a higher risk for pregnancy complications in order to tailor their care accordingly, thereby decreasing maternal and neonatal mortality nationwide.

-

In the Afya-Tek program on mainland Tanzania, we’re working with Simprints to integrate biometric identification into our continuity of care program. Fingerprint ID scanning will allow the system to uniquely and accurately identify patients within and across levels of the health system and streamline longitudinal care and referral completion.

Digital health is not just about apps that make the correct diagnosis. It is not just about digital records or arranging transportation or even better communications. Digital health is about all these things and how, when responsibly integrated with the human processes of an existing health system, they can act as tools to get families the care they need. It helps create efficient systems and processes, which lead to behavior change, which then enables actors at all levels of the health system to be more effective and efficient. It is how a nurse like Jalia can help diagnose and treat a 6-year-old boy like Khari from an otherwise deadly disease. In short, digital health is the integrating tool that enables community health workers to do their job; indeed, it is the very link that joins the pieces of the health system together.

References

McCann, D. (2012). A Ugandan mHealth moratorium is a good thing. http://www.ictworks.org/2012/02/22/ugandan-mhealth-moratorium-good-thing/. Accessed 1 May 2020

Bahia, K., & Suardi, S. (2019). The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity (GSMA Connected Society, pp. 1-60, Rep.). London, UK: GSM Association.